Ideas

We explore big ideas through design. Research is integrated into our projects and practice, where we test and develop ideas big and small through design, site experience, conversation, and activism.

To cohabit is to live together in an intimate relationship, to dwell with one another and share the same place.

It is vital to expand architecture beyond “design for us,” beyond a built environment conceived exclusively for human consumption and comfort, to address the wider global ecosystem as a shared space for all species. How can we expand the traditional notion of client to include perceived human and animal, preserving and expanding habitat for all?

Today’s world is unpredictable — climate change, biodiversity loss, and the ecological shifts are deep, underlying trends that shape our cities and our world.

How can designers make positive change?

Historically, urban development has concealed landscape systems – burying waterways, flattening topography, and removing vegetation.

But even the most urban of sites hold potential – we aim to advance a new aesthetic that emerges from the desire to revive: one grounded in heightened eco-awareness, and the idea of landscape as a material practice rooted in the geological, hydrological, and social systems that sparked their formation.

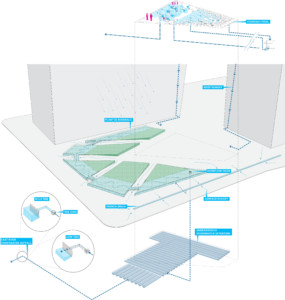

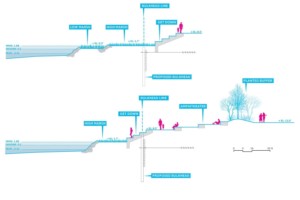

Water Based Urban Design

Public spaces cannot only carry programming and recreation, they can literally hold water. At First Ave Park, we designed an inhabitable landscape that accommodates multiple types of water through the layering of above-grade and below-grade infrastructure. The design holds stormwater from the site and building, protects against flood waters during Hudson River surge events, and expresses water at the surface in the form of an interactive fountain.

Read about the many roles of water in SCAPE’s First Ave Water Plaza.

Reforest The Street

Vegetation is critical to ecosystem diversity, yet in urban areas vegetation is often limited and monotonous, lacking layered structure and variety. Designers have the opportunity to shift aesthetic values and embrace textured landscapes that favor biodiversity and urban-ecological value. These landscapes look different – embracing seasonality, texture, habitat value, and urban tolerance. At Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus we brought the forest to the street, designing an absorptive and tiered system of planting beds that support a cosmopolitan mix of plants adapted to the urban environment, a tiered planting of ephemeral wildflowers, perennials, woody shrubs, understory trees, and canopy trees.

See the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus streetscape for the trees in action.

Infrastructure As Amenity

At SCAPE, we think of infrastructure as functional, performative, and highly engineered. But how does it integrate with our broader environment, not merely solve narrowly defined problems? Can infrastructure be performative an adaptive, while being a place of play, recreation, and escape?

Read here how Lexingtonians value multi-purpose infrastructure in Lexington, KY, where a recreational trail and a sewage storage tank intersect.

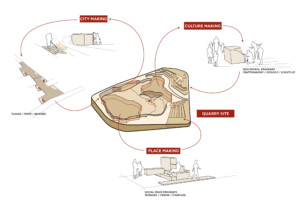

Working Landscapes

Urban landscapes can produce valuable goods and services- minerals, foods products, clean water – while creating new forms of public space. Can active landscapes of production and extraction co-exist in urban environments? The Be’er Sheva Quarry Park celebrates the act of digging, reactivating an abandoned quarry with small-scale stone extraction to catalyze forms of public interaction and stewardship.

Dig deeper and read more about SCAPE’s collaboration on Be’er Sheva Quarry Park.

Redefining Beauty

“Rather than the postcard-perfect iconic images of sublime rocky wilderness that affirms our country’s past mythology, nature at the edges of towns and cities offers direct experience of natural processes and their reciprocal role in sustaining urban life. They are crucial to evolving our national ideology in response to environmental realities and in generating a joint approach to urban and natural systems. The muddy flats at Gateway offer a new, post-picturesque aesthetic to guide the remaking of America’s increasingly urbanized landscape.”

Excerpt from Kate Orff, “Cosmopolitan Ecologies” in Gateway: Visions for an Urban National Park, photographed by Laura McPhee.

Process as Practice

“I think of landscape architecture less as a professional discipline (making drawings and charging for them) and more as a way of generating new cultural and environmental narratives… I don’t want to say my approach is radical, but it is philosophical and idea-driven. So, for better or for worse, I don’t come at landscape architecture from a service point of view but from a process point of view. The goal is world-changing, but the methodology and practice is regional: SCAPE is trying to help rebuild the New York bioregion one site at a time.”

Excerpt of Interview of Kate Orff from “Design Practices Now, Vol. II” in Harvard Design Magazine, 2010.

Adaptive Management

Adaptive management is an iterative process for decision making in the face of uncertainty. How can design processes organize around adaptive management principles to create more flexible and responsive projects? This thinking permeates many of our larger infrastructure and planning projects, but also applies to smaller sites. Even residential work can apply ecological planning principles – in Sag Harbor, NY, we return annually to monitor a restoration project on the edge of Long Island sound. Each year reveals new environmental dynamics – variable levels of deer pressure, invasive plant emergence, coastal change, and shellfish density all change from season to season, year to year. Maintenance and management of this landscape requires trial and error, flexibility and experimentation.

Read more about the changes in Cove Cohabit here.

Mutualism by Design

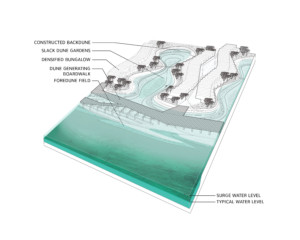

Can ecosystems and urban systems be mutualistic? Often human needs and ecological needs are at odds – urban development destroys habitats, ecosystems that remain are fragmented and substantially altered. In highly altered systems, can new mutualistic systems be introduced that encourage the success of both human and non-human inhabitants? In the Far Rockaways, named after a Lenape term meaning ‘Place of Sand,’ we explored urban ecological mutualism through a design of a new housing typology structured by a layered dune system. Constructed dune ridges would protect and elevate critical site infrastructure and utilities, while dune lowlands, or slacks would act as coastal gardens and habitat corridors connecting larger dune reserve areas with the shoreline. A layered, ocean front dynamic dune would migrate around the boardwalk, adding layers of protection while creating a unique site topography day to day.

See more Dune Design here.

Do No Harm

Some ecological externalities are obvious, others are harder to see. How can we be more fully aware of how our projects are perceived by non-human species? How can we prevent our work from harming the daily patterns of non-human life? Think like a bird with the NYC Audubon Bird Safe Building Guidelines, where the urban environment is interpreted through the experience of an avian cohort. Simple material substitutions, like birdsafe glass installed along the Hudson River flyway at the Columbia Medical Center landscape, reduces the chance of bird strike without compromising panoramic river views.

Get a bird’s eye view at NYC Audubon BSBG and the testing of new materials at Columbia Medical Center Building.

Design Values

Design adds value, increasing property values and tax bases while catalyzing new activities in the urban realm. But design is also shaped by values, ethical and moral, personal and professional. At SCAPE, design values stem from a deep appreciation of the natural systems and cycles that shape the urban landscape, and the ability to use landscape architecture as a tool to think broadly about the integration of ecology into the built environment.

Hear Kate Orff talk on Design Values at the University of Kentucky College of Design lecture series.

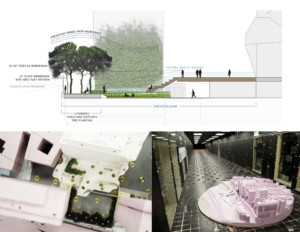

Human Microclimates

Urban plants and animals must endure some of the city’s most severe microclimates – sunbaked concrete sidewalks emitting extreme heat, windy and exposed rooftops, dry soils shaded by skyscrapers. People are also impacted by the extremes of the urban environment, and landscape architects are often asked to mitigate and design within these harsh conditions for the benefit of people and animals. Iterative design processes and environmental evaluation tools can help design and shape more biodiverse urban microclimates that accommodate people. At the Columbia Medical Center Graduate Education Building, an iterative design process with the Boundary Layer Wind Tunnel Laboratory in London, Ontario resulted in the design and location of a tiered system of windbreaks and planted screens that enabled everyday comfort on site and expanded the palette of adapted plants.

Learn more about the design process for the Columbia Medical Center Graduate Education Building here.

Park Raising

Regenerating underutilized public space alongside community members as co-builders is a rare event in urban areas. By working with underserved communities to understand their direct needs, we believe design projects will have the most impactful results. In East Harlem, we worked with partners at NYRP to engage a group of neighborhood residents in a design-build process that began with a public charrette and culminated in a “park-raising” day. The park design needed to accommodate young children, gardeners, teenagers, athletes, and seniors in less than a quarter of an urban block. Over a matter of months, volunteers came together to share ideas, review drawings, and shape the design of the park into a multi-use public commons. Perhaps what we need in our urban ecosystems are not merely more parks, but more “raisings” that regenerate underutilized spaces while creating and strengthening social infrastructure.

Read more about the neighborhood park at 103rd St Community Garden.

Intergenerational Space

Spaces are typically programmed for just one subset of the population—old or young, not both. Spaces that serve multiple age groups can be successful recreational areas, and can forge new relationships between often-stratified members of society. The renovation of Blake Hobbs Park, known at SCAPE as Blake Hobbs Play-za, was an opportunity to test this idea, and a design space that could be used by members of the adjacent community – including seniors from an adjacent NYCHA senior living facility, new residents living in recently constructed affordable housing, and K-8 students attending the Harlem RBI Dream Charter School. The project transformed an existing asphalt playground into a dynamic public commons that serves people of all ages.

Read more about the intergenerational play-za here.

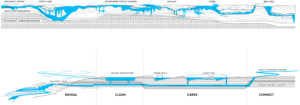

Next Generation Infrastructure

American cities face common problems – obsolete water management systems, fragmented public space networks, and ecologically sterile urban environments are pervasive issues regardless of scale and size. SCAPE imagine new models for next generation infrastructure, designing systems that hybridize engineering, transportation planning, and ecology. But infrastructure also needs a storyline – our Town Branch project defines next generation infrastructure through the lens of hydrogeology, tying together the cultural and ecological through a stone called karst.

Follow the water and read more about SCAPE’s Town Branch Commons project.

Waterfront Parks?

Pastoral notions of park do not adequately serve our city’s wide range of urban animal inhabitants, nor do they accommodate the changing coastal conditions of the urban water interface. Design should move beyond the ubiquitous lawns and paths that dominate our waterfront parks and our zoning legislation, and make room for dynamic edges that create habitat and improve maritime ecology.

Hear more about breaking down the bulkheads in Gena’s talk Waterfront Parks? at the RPA Summit on Climate Change, and see new forms of waterfront park here.

Listen to Geology

We aim to improve urban water systems and hydrological performance, yet these systems are buried underground, invisible to the public, and let’s face it, a little boring. How do you generate excitement and interest in a culvert? Catalyzing productive dialogue on urban infrastructure is a design challenge of the 21st century – the Town Branch Water Walk is one example of a lighthearted and educational approach to interpreting the urban subterranean environment through audio tours, lane closures, and watershed models.

Water Walk with us and read more about the Town Branch Water Walk project here.

Maritime Cohabitat

Can species be agents of urban change? Hear Kate’s TED Talk on Oyster-tecture, where she shares a vision for the whole of New York Harbor as an intensively managed co-habitat. The project moves away from a harbor defined by human dominance, recognizing the essential ecosystem services our waterways once performed — and could perform again. The massive engineering efforts of dredging, dumping, bridging, infilling, and walling off would yield to processes of interspecies engagement with reef-building, oyster-cultivation, and FLUPSYs (floating upwelling systems, or oyster nurseries). The new processes would create the contexts for a landscape that truly fosters multispecies habitation.

Learn to live with oysters and watch Kate’s TED Talk on Oyster-tecture.

Take Your Time

Long term forestation practices are useful and underutilized techniques in the urban and rural landscape. While not commonly applied on large capital projects, forestation techniques can play a role in creating landscapes over time that increase in habitat value. At the Blue Wall Center, the team was commissioned to design a future environmental and interpretive center at the Blue Ridge Escarpment. This long term vision and capital project was supplemented with an ‘advanced set’ proposal, to stabilize the highly disturbed site through forestation techniques of whip planting supplemented by nurse trees, and build soils through native meadow seed mixtures and new mowing regimes. While the capital campaign and project have stalled, the project lives on as a reforestation experiment, where the low-budget intervention grows in ecological value over time.

Read about slow change at the Blue Wall Center.

In-Situ Study

How can active marine industrial areas support underwater life? At the SIMS pier, our team developed a temporary in-situ design experiment to test this question. Monitored in collaboration with Michael Judge of Brooklyn College, the project installs fourteen community-made fuzzy rope panels and a series of ECOncrete tiles supplied by SeArc Consulting off the SIMS pier in Sunset Park, Brooklyn in March 2013. The fully functioning barge mooring pier now supports a diverse and changing composite of aquatic life; by June of 2013 the fuzzy rope panels supported between six and twenty blue mussels per linear foot and a host of associated species including green crabs, colonial and solitary tunicates, barnacles, amphipods, algae, and sea squirts. While the installation has a maximum lifespan of five to seven years and is considered temporary, it reveals how even active industrial shorelines can function as critical parts of New York City’s coastal habitats, and how simple materials can be repurposed as habitat probes.

See monitoring in action on our Facebook post of the project.

Participatory Habitat

Urban Ecology invites participation in habitat design across all scales. For the Fuzzy Rope Weaving Evening, we welcomed friends, local business owners, and watershed activists to weave simple and replicable habitat panels in a participatory habitat building event. Fuzzy rope, a polypropylene material explored in the Oyster-tecture proposal, is a tactile cable used in the aquaculture industry to cultivate mussel colonies — it adds much-needed underwater surface area to depleted shorelines and a microstructure for habitat recruitment. This material, applied as vertical net structures along an industrial barge-mooring pier, was tested as a temporary underwater habitat near an active recycling facility. Over thirty volunteers thought it worth a try, and their many hands fabricated fourteen fuzzy rope panels, seven intertidal and seven subtidal, which were later installed at a SIMS Metal Management site in Brooklyn. SCAPE interns designed a shareable pamphlet that described the weaving process and invited others to design and monitor their own in-situ experiments.

See the weaving evening here.

Artificial Habitat Assessment

To design below the waterline, we need to know what lives there and why. Our shorelines and seafloors are constantly under transition – oyster reefs have turned to sandy bottoms, marshes to silted sea floors, and beaches have shrunk and expanded. The environment is constantly in flux, and to imagine new potential habitats it is critical to look not only at what exists on a site, but what life exists on reference habitats to inform our proposed designs. In our Living Breakwaters project, where we propose a protective network of breakwaters along the South Shore of Staten Island, we looked for nearby reference habitats that might help us understand the types of species that the breakwaters will attract and the localized habitat conditions they can create. We found such references in nearby channel markers, built atop large submerged rock piles, like lighthouse bases and nearby piers. SeArc Marine Ecological Consulting took a dive to assess these constructed ecosystems, and found that these environments and the areas around them host a much wider cast of maritime characters than simple sandy bottom habitat currently in the project area, including blue crabs, branching sponges, bryozoans, and clams.

Go for a dive with us, and read more about the Living Breakwaters Project here.

Living Infrastructure

Landscape design can play a role in the restoration of shellfish habitat in the New York Harbor. Eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) and ribbed mussels (Geukensia demissa) provide numerous ecosystem services. Both species of bivalves are filter feeders and can improve water quality by facilitating the removal of excess nitrogen and other pollutants from the water column. A single oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day (NY/NJ Baykeeper, pers. comm.). Oysters are a keystone species in the ecosystem, and reefs in particular increase the availability of habitat for a wide array of marine organisms by providing spatially complex substrate and mosaic-like topography. They also can function as wave attenuators, thereby helping to mitigate the effects of storm surges (New York-New Jersey Harbor Estuary Program 2009).

Excerpt from Kate Orff, “Shellfish as Living Infrastructure” in Ecological Restoration, 2013.

Cohabitat As Policy

At SCAPE, we see our pilot projects contributing to larger systemic and policy reform. How can cohabitat techniques become formally integrated into New York City plans and polices and impact larger scale design? What research goals and knowledge gaps prevent us from implementing constructed wetlands, breakwaters, and ecologically enhanced bulkheads? What regulations and geophysical conditions limit their application? SCAPE contributed towards the Coastal Green Infrastructure Research Plan for New York City, which addresses these questions and strikes a path forward for implementing coastal green infrastructure at an urban scale.

Get into the research here.

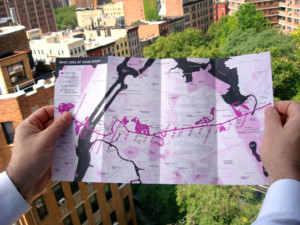

Landscape Literacy

To engage is not to just propose solutions but to increase the perception and understanding of place. Lived, direct experience with the physical landscape and its long-term stewardship leads to better outcomes. How do we make tools for others that enable new readings of our everyday environments? A project that democratizes the map, integrates new social technologies and includes countless fun excursions is the Urban Landscape Lab’s Safari 7, a platform from which to view, celebrate, research, and exchange ideas about urban nature. At the start, we asked: What is urban nature? How can it be perceived and engaged by a broad cross-section of people? How do natural and urban systems coexist within megacities? In this free and downloadable podcast tour of urban ecology along the No. 7 subway line, we aimed to redefine and expand the role of landscape in interpreting the urban environment and to move beyond the static media of “report” to engage students and the public in dialogue about the built environment through social networking tools.

Get on board and take the Safari.

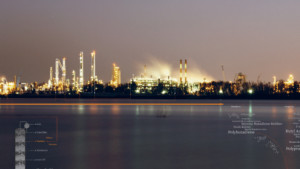

Activism

We design in a world of constant political and social change. As designers, we have the capacity to imagine different patterns of action, generate a magnified understanding of the interconnectedness of systems and processes, and scale up our work to effect larger behavioral change. And we need to do it now. But this type of project is not commissioned by a specific client or municipality in a typical Request for Proposals. Rather, it is a pervasive stance of activism that can be brought to bear on all our endeavors. “Petrochemical America”, an exhibition and publication project that investigates the social, ecological, and economic impacts of the Southern Louisiana petrochemical industry, works beyond client commission to understand the complex conditions of this devastated landscape. Activism here is translated as ‘looking harder,’ describing the hidden conditions at hand and revealing possible triggers for future change.

Look closer at the Petrochemical Project Room exhibition here.

Seeing

“The thing with landscapes is it’s so hard to see things.”

Excerpt from “What Kate Orff Sees” in Landscape Architecture Magazine, 2012.

Urban Storytelling

“The goal of urban design is to not just design a thing but actually to design participation itself. To advance the conversation of urbanism far beyond what is known and to try and engender what should be done.”

Traditional legally mandated models of participation polarize the public into those ‘for’ and ‘against’ a project. Yet designers are developing new tools for community engagement that reveal site narratives and tell stories, opening up new lines of communication and building stronger coalitions that support and shape complex projects.

Hear the rest of Kate Orff’s talk on the importance of storytelling in design at the Columbia GSAPP Urban Storytelling Symposium.

Tools of Engagement

Scaling up community engagement means creating tools for others to use, tools that grow exponentially outward and build a shared knowledge base towards common goals. In the project Living Breakwaters, an oyster-gardening manual was created in collaboration with the graphic design firm MTWTF for distribution and use in New York City schools that described the New York Harbor School’s techniques for raising urban oysters in support of the Billion Oyster Project. Now used in classrooms throughout Staten Island, this small pamphlet helps classrooms connect with the water, and builds a larger research and stewardship base for future large-scale ecological infrastructure.

Making Publics

“I try to practice landscape architecture as a stance, a stance of activism, with the idea that we can choreograph landscapes that promulgate new civic life. I’m interested in building publics not projects, and I’m interested in places where people and citizens are actively involved in making spaces and resetting ecologies.”

Hear the rest of Kate Orff’s declaration on Landscape Architecture at the 2016 Landscape Architecture Foundation Summit.

Connecting the Dots

“I think a major challenge of making change is being able to visualize issues and to have an informed conversation about these issues… My hope is that by integrating emotion and analysis, photography, research, and speculation, the book can play a role in sparking a deeper discussion about the future of energy and our shared climate and the landscape that we have made. The sort of fragmented way of thinking has gotten us to this point, but to move forward into a cleaner, more just energy era we’ll have to have a different, more synergistic approach. We tried that with this book, and hopefully it will spark other sorts of collaborations and exchanges.”

Read more about Kate Orff and Richard Misrach in conversation about their book, Petrochemical America, 2014.

Landscapes of Public Health

“This paradigm of public health and meshing that with urban design thinking is just so key. Because it’s about understanding these interrelationships and breaking out of the intimacy of the doctor-person relationship and thinking about broader public health… What we’re trying to do is interweave these patterns of public health, energy generation, and urban design together.”

Hear more from Kate Orff and Helen Caldicott’s lecture, “Who Cares?” in conversation about toxicity, the body, and the American landscape.

Social Activism

To study landscapes is to study the communities that inhabit them, from coastal metropolises to underserved industrial zones. As designers, we can use our case studies, tools and practices to connect the dots between peoples’ lived experiences and regional problems, in order to design solutions for regional change. This type of work requires a commitment to understanding a region’s history, present, and future.

In October of 2016, SCAPE led a tour with the Dredge Research Collaborative and other partners along River Road, Louisiana’s Petrochemical Corridor. The tour, titled “Thicker Than Water: A Sediment and Petrochemical tour of the Lower Mississippi”, features sites of ecological and social conflict between industry, natural processes, and local communities. Building off Petrochemical America and the work of Dredge Fest Louisiana, the tour provides a closer look at the hidden and places-based consequences of American consumerism and large-scale ecological change. Watch here.

Read more about how Petrochemical America has continued to be a form of social activism here.

Knitting Circles

“In a culture marked by fragmentation, knitting is an apt metaphor and shared activity. The knitting project was a means to reach out to people of diverse ages, to bring them together in social and collaborative ways, and prod them to think about water quality and their shared harbor. Every action has the potential to pull together an engaged citizenry. Engagement itself is a process, a project and a product. Community events — following either conventional or unexpected formats — must be woven into the DNA of the design process itself.”

Excerpt from Kate Orff, Toward an Urban Ecology, 2016.

Read more about the crowdsourced craft project here.

Design Climate Policy

Heat waves, drought, heavy precipitation, hurricanes — all of these unpredictable weather patterns need to be considered for the future. Designers need to confront traditional static and mono-functional approaches to infrastructure, and to understand that there is not a panacea solution to climate change. In New York, we worked on a city-wide plan for rebuilding and resiliency planning post-Sandy — the SIRR Report (Special Initiative in Rebuilding and Resiliency). As designers, we emphasized the importance of including several different strategies for enhanced coastal protection and the growth of carbon-sink ecosystems — a layered approach. This city-scale collaboration is not an implementation mandate; rather it provides a framework for consensus-building and organizing around the risks of future climate change impacts, as well as establishes New York City as a leader in resilient coastal design and planning.

Read more about the SIRR Report plan here.

Ecological Infrastructure

How can ecological infrastructure be seeded to grow along with the future threat of climate change? How can planning for disaster incorporate multi-purpose infrastructure, without reverting to traditional norms of solving one problem while ignoring the related and resulting issues it catalyzes? Living Breakwaters aspires to design infrastructure of the 21st century that reduces risk to vulnerable neighborhoods, revised ecosystems, and connects neighborhoods to the shore. The project alone does not stop flooding, but builds an ecologically generative and lower-risk shoreline over time.

Read about the large-scale concept and see how it’s being implemented.

Planning for Climate Change

“Issues as massive as global climate change can feel well beyond our capacities to effect positive outcomes by bringing together large-scale strategic planning practices and community-based participatory initiatives, expanding environmental awareness, in ways that enable change. Yet we believe that the concept of the designed neighborhood-scale landscape is a manageable scale of thought and action, which can spur a larger public debate about achievable solutions and collective responsibilities necessary for such achievement. From here we can productively scale down (to the unit of individual behavior) and up (e.g. to the frame of regional politics).”

Excerpt from Kate Orff, Toward an Urban Ecology, 2016.

Hear Kate and Naomi Klein discuss planning for climate change in a lecture at Columbia GSAPP.

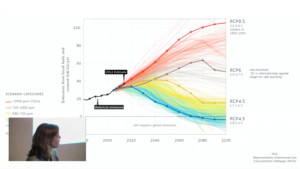

Speaking Out

“I am motivated by these two things: What are the real and interesting questions now, and what can design do? … Number one would be climate change… will we be changing the trend of the graph, or not? I find this motivating.”

Hear Kate contextualize SCAPE’s work in relation to climate change at her “SCAPE” lecture at Columbia University.

Work Across Scales

Climate change requires a multi-scalar approach. We explore ideas across scales big and small to address climate issues, from micro-installations and ecological experiments to macro-scale planning, analysis, and design.

Jump scales with Gena at the Gowanus Design Summitt.

Back to the Future

Site history can inform future landscape proposals without replicating the past. Much of our work looks to pre-industrial age agriculture, aquaculture, and technology to inform future relationships with the land and water. In New York City’s Staten Island, reefs and leased oyster beds once extended across the shallow water flats of Raritan Bay, reducing storm impacts and filtering water. Historic images show fishermen tonging for oysters in leased beds along the coast of Mt. Loretto and Lemon Creek, once a critical economy of the South Shore. Over time, shellfish populations declined due to sedimentation, water contamination, and channel dredging, though efforts are underway to restore this keystone species to the harbor. Looking back reminds us that dramatic change in place, environment, and ecosystem is part of understanding current urban ecology, and critical in projecting forward newly modified cohabitats and communities.

See how Staten Island’s past is impacting its future.

Dark Matter

“Projects for Waterproofing New York involve a deep dive into the dark matter, meaning that most of the hard work is not in the form of visible landscapes that we can inhabit or Photoshop™, but rather in the form of invisible regulatory, administrative, permitting, and political systems that determine how, what, and where we build. Nowhere is this more apparent than in designing in and around our living water bodies. One oyster, one thousand permits. The real prerequisite for change is an evolved regulatory structure that learns from the past, spanning lessons learned from early pre-industrial aquaculture techniques to more recent updates to our enforcement of the Clean Water Act. Change comes, but is slow… Civil works of the sort needed post-Sandy will require a brave new world of not only public space and collaboration, but permitting.”

Excerpt from Kate Orff, “Dark Matter” in Brandt and Nordenson, Waterproofing NY, 2016.

New Energy Landscapes

“What remains to be collectively imagined is what a shift away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy forms would mean in the future in terms of generating a new American landscape aesthetic of promise and productivity, whether in the form of solar panels arrayed in the desert, rows of plantings of poplars and willows for phyto-remediation and biomass energy offshore wind farms on the horizon, or wave energy off our coasts. Americans together can start imagining the country as it could be and come together with the resolve that in order to reclaim America, The Beautiful, we need to actively transform the Big Oil landscape we have made — from lawn to habitat gardens, from black roofs to glowing solar panels, from single family isolated home to clusters and walkable neighborhoods.”

Excerpt from Kate Orff’s article “Toward A New Energy Landscape” in the Huffington Post.

Experimenting with Engineers

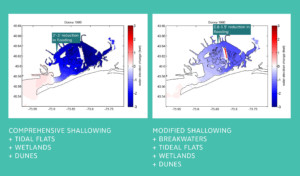

Design/engineering collaborations open up new possibilities for climate responsive design. In Jamaica Bay, years of research and formal and informal collaboration with Phil Orton led to the development of the Bay Nourishment Jamaica Bay strategy proposed early in the Rebuild by Design competition. In these studies, restoration of historic wetlands was compared with channel shallowing and modification, which revealed that bathymetric channel changes had significantly more impact on the reduction of hurricane induced flood levels than wetland restoration alone. Dr. Orton and partners advanced this work into research published in the Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, suggesting that shallowing is an effective technique at reducing ‘fast-pulse’ storm surges, and should be considered as one possible strategy for climate resilience in Jamaica Bay.

Read the “Channel Shallowing as Mitigation of Coastal Flooding” paper in the Journal of Marine Science and Engineering.

Everyday Design

While extreme events shape the dialogue around climate resilience in coastal regions, many large-scale infrastructures designed to protect against these events neglect the experience of the everyday and sever a community’s relationships with water. Understanding and amplifying what is valued about a place is critical for implementing adaptive infrastructure of the future. Simple events, like the Raritan Bay Festival, help us understand what is valued about the Staten Island shoreline and how these uses and experiences can be maintained and enhanced in the future.

Celebrate Staten Island’s everyday shoreline at the Raritan Bay Festival with the Living Breakwaters team.

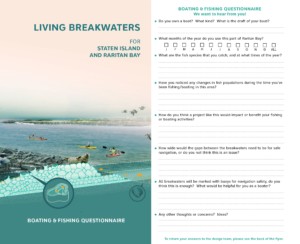

Ask Around

We often learn the most about a place by speaking to the people who use the space the most. Much of our waterfront design work involves getting feedback from unique audiences that don’t always show up at typical public meetings because they are ‘working’ on the waterfront. How does a clammer use the shore? A scuba diver? A surf fisherman?

Tell us how with our Living Breakwaters Shoreline and Fishing Questionnaire.

Pushing Restoration Boundaries

We live in a city of complex ecological systems where infrastructural built forms meet opportunistic living organisms. Many terrestrial and aquatic species have been severely impacted by habitat loss due to the operations of our shifting urban landscape, but through varying scales of ecological restoration, we can begin to test the evolution and adaptation of species once present in our surrounding environment. SCAPE has participated in several local restoration efforts. In the water, SCAPE has partnered with Brooklyn-resident and environmentalist, Bart Chezar (who was also featured in Towards an Urban Ecology), wading below the waterline to plant eelgrass in Sunset Park’s Pier 5 and using a GoPro to monitor the underwater Fuzzy Rope installation off of the SIMS Municipal Recycling Facility. On land, the team has toured the Native Greenbelt Plant Center in Staten Island to learn about locally sourced native seed stock and understand their role in creating resilient plantings adapted for environmental conditions within the region.

Through these collaborations, SCAPE sets out to observe and document the unique moments of co-habitation and embrace the complexity of change that comes with working in dynamic urban ecological systems.

Read more about the most recent planting trip at Pier 5 here.